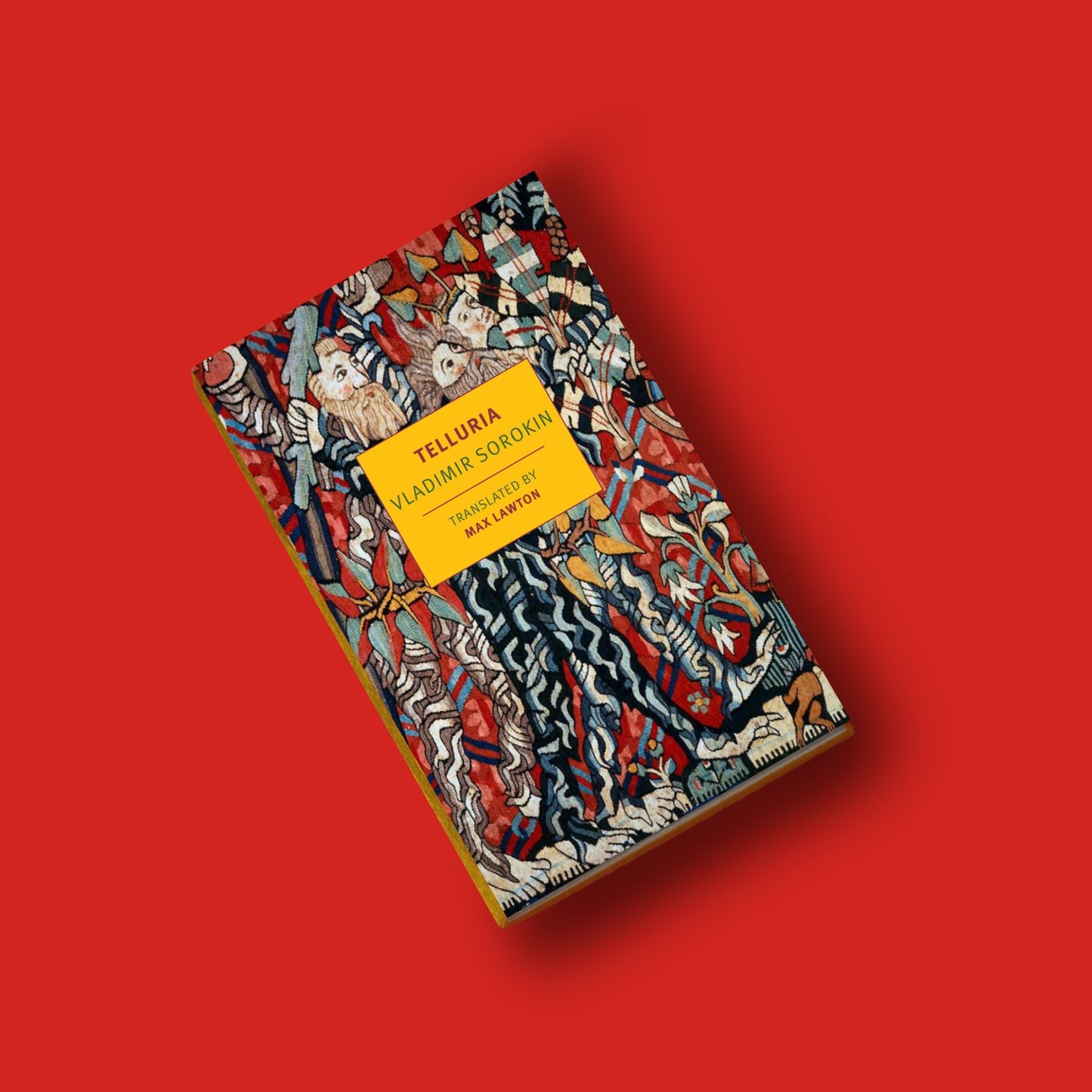

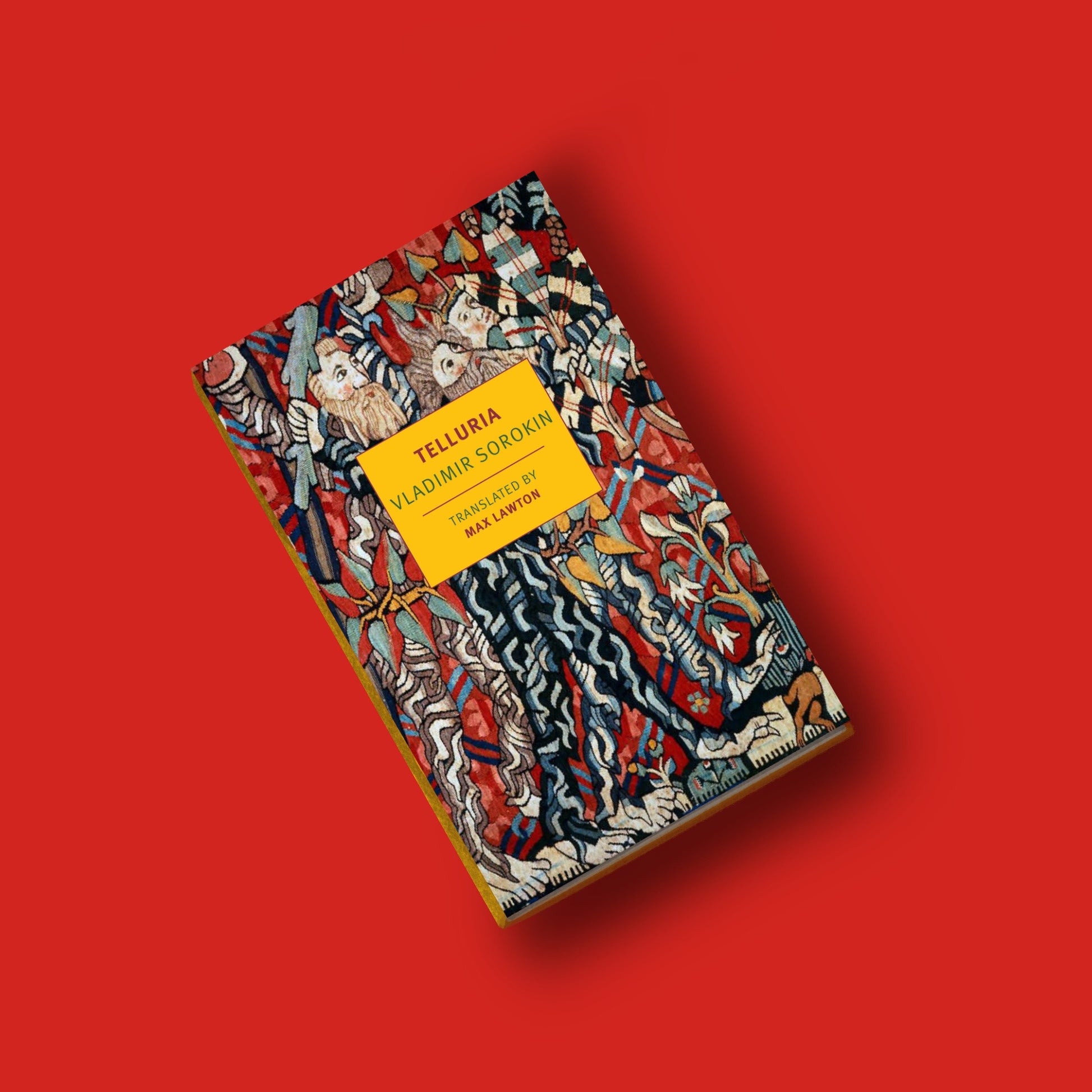

Telluria, by Vladimir Sorokin

Couldn't load pickup availability

Telluria is set in the future, when a devastating holy war between Europe and Islam has succeeded in returning the world to the torpor and disorganization of the Middle Ages. Europe, China, and Russia have all broken up. The people of the world now live in an array of little nations that are like puzzle pieces, each cultivating its own ideology or identity, a neo-feudal world of fads and feuds, in which no one power dominates. What does, however, travel everywhere is the appetite for the special substance tellurium. A spike of tellurium, driven into the brain by an expert hand, offers a transforming experience of bliss; incorrectly administered, it means death.

The fifty chapters of Telluria map out this brave new world from fifty different angles, as Vladimir Sorokin, always a virtuoso of the word, introduces us to, among many other figures, partisans and princes, peasants and party leaders, a new Knights Templar, a harem of phalluses, and a dog-headed poet and philosopher who feasts on carrion from the battlefield. The book is an immense and sumptuous tapestry of the word, carnivalesque and cruel, and Max Lawton, Sorokin’s gifted translator, has captured it in an English that carries the charge of Cormac McCarthy and William Gibson.

Praise for Telluria

"Sorokin is both an incinerator and archaeologist of the forms that precede him: a literary radical who’s a dutiful student of tradition, and a devout Christian whose works mercilessly mock the Orthodox Church. It’s this constant oscillation between certainty and precarity, stability and chaos, beauty and devastation, homage and pastiche, plenitude and rupture that makes Sorokin’s fiction unique." —Aaron Timms, The New Republic

"Telluria. . . is a dystopian fable set in the near future, as Europe has devolved into medieval feudal states and people are addicted to a drug called tellurium. Through the smokescreen of a twisted fantasy teeming with centaurs, robot bandits and talking dogs who eat corpses, Sorokin smuggles in a sly critique of contemporary Russia’s turn toward totalitarianism." —Alexandra Alter, New York Times

"In Sorokin, Russia found its Pynchon." —Vladislav Davidzon, Bookforum

Translated by Max Lawton

Paperback

352 pages.